The BBVA Foundation premieres Out of Control. Reports on the Atomic Bomb, a work by video artist Beatriz Caravaggio

Out of Control. Reports on the Atomic Bomb, a film by Beatriz Caravaggio, addresses the issue of nuclear weapons. The BBVA Foundation commissioned the work from the artist before the start of two dramatic global events: the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, due to which the threat of nuclear weapons has resurfaced as an international concern. The film will be screened in the MULTIVERSO space, in the Foundation’s Madrid headquarters from 2 June 2023 to 30 June 2024, Monday to Sunday (including public holidays) between 10.00 a.m. and 9.00 p.m., with admission free to all members of the public. It will also travel to the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts, in the frame of the two institutions’ joint program of support for video art creation.

5 June, 2023

On the eve of the opening, a presentation took place with the participation of Rafael Pardo, Director of the BBVA Foundation, Miguel Zugaza, Director of the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts and Beatriz Caravaggio herself. Also attending the event was Japan’s Ambassador to Spain, Takahiro Nakamae, and a sizable representation of our county’s scientific and artistic communities.

“We wanted to invite a group of prominent figures from the worlds of science and the arts, institutions and the media, along with the members of the team working on the film and friends of the author’s,” said Rafael Pardo addressing the public before the film’s first screening in the Multiverso space of the Marqués de Salamanca Palace.

For the Foundation’s Director, Beatriz Caravaggio’s work is “an impactful narrative that revolves around the aggregate – and paradoxical – result of the confluence of a powerful capacity for analytical study and control, characteristic of scientific practice in specific domains, and the latent lack of control existing in the social application of the results and promises of science, in the absence of dialogue and debate on ethical, civic and environmental values and approaches. With its minimalist language that avoids both explicitly moralizing and criticizing or rejecting the cognitive pillars of science, this is a singular piece of modern filmmaking of enduring cultural and ethical significance and widespread relevance to other cases. It also stands as proof of the immense value of the artistic gaze when turned upon issues of overarching importance.”

On 16 July, 1945, the first atomic detonation took place in the New Mexico desert. The Trinity Atomic Test involved a 20-kiloton explosion that demonstrated hitherto unseen destructive power. Just 21 days later, the Little Boy bomb hit Hiroshima and, three days after that, Fat Man landed on Nagasaki. In these two cities 200,000 people died.

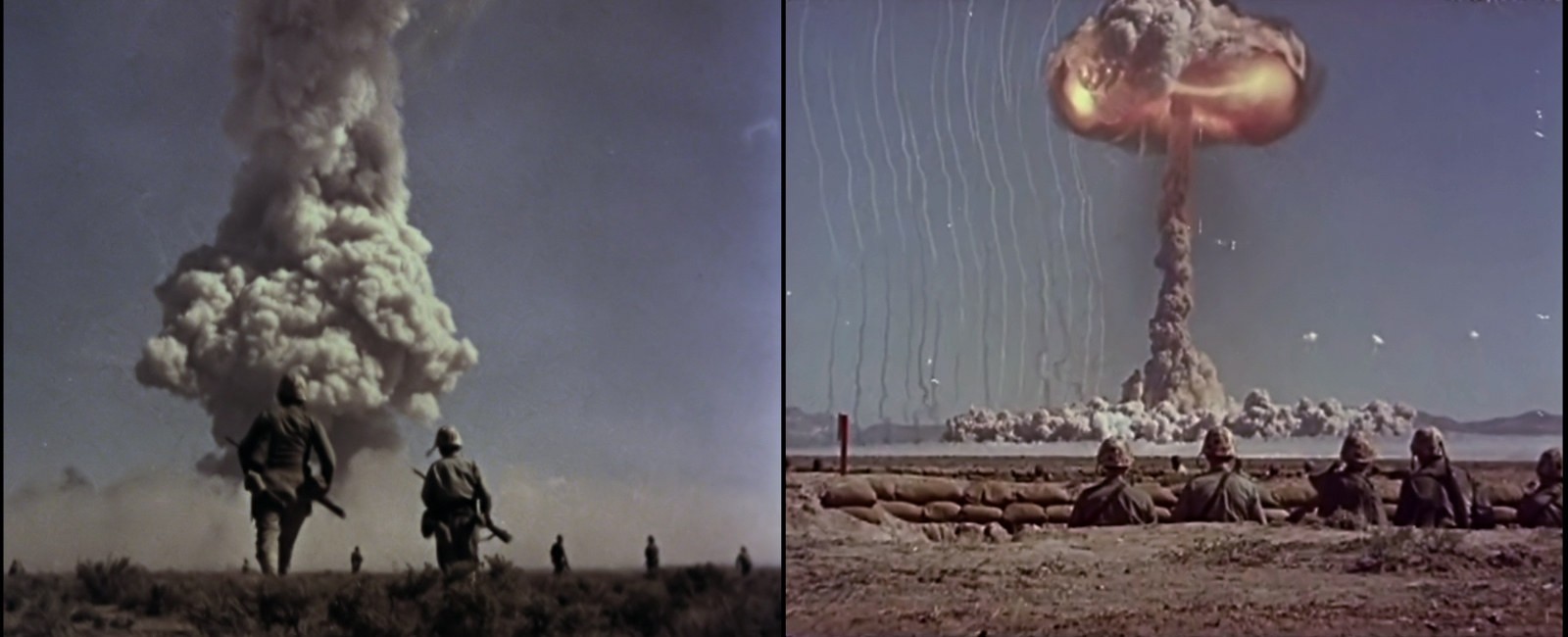

Since then, the United States, the former Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have conducted more than 2,000 nuclear tests. Governments systematically filmed these tests to facilitate scientific study of the detonation process, accumulating thousands of audiovisual archives. And hundreds of classified documents were written dissecting the entire nuclear operation. Nothing was left undocumented or unmeasured in a series of reports in which human beings, animals and life itself were merely formal objects for analysis and intervention. Everything to do with ethics, respect for the principle of dignity and the preservation of life was omitted from the scope of consideration of these thousands of pages.

We are all aware that the applied power of knowledge can bring about effective and much-needed solutions to pressing problems, but that this same power, in certain spheres, can also lead to danger. The precision and control of nuclear tests, captured in objectified images and reports that provide the subject matter for Out of Control. Reports on the Atomic Bomb resulted in vast stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction, the consequence of an unstoppable arms race that was genuinely out of control. Science is a transformative and fundamentally liberating force. However, the continuity and improvement of life on Earth also depend on dialogue with other cultural constructs, from the humanities to the arts, and on the involvement of plural social forces in all those decisions that involve existential risks on a global scale.

This film was commissioned from video artist Beatriz Caravaggio by the BBVA Foundation. The commission was made before the advent of two dramatic global events: the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, due to which the threat of nuclear weapons has resurfaced as an international concern. Its release coincides with the G7 Summit being held in Hiroshima on the initiative of Japan, to symbolize this latent threat while calling for peace in Ukraine.

The artistic potential of a latest existential threat

“When I received the commission,” the artist recalls, “the BBVA Foundation proposed three subjects to me, from which I chose nuclear weaponry because of the huge consequences it has had, and still has, for humanity and life on Earth, as a latent existential threat, and also because I thought it held out a lot of artistic potential.”

Caravaggio had created a previous work under commission from the BBVA Foundation, Different Trains, based on Steve Reich’s piece of the same name. The composer praised her film as the best visual translation of his music and an outstanding work in its own right. For its author: “There is some continuity with Different Trains, as the events narrated belong to the same period, the 1930s and 1940s and the Second World War, the Holocaust and the rush to develop the atom bomb for fear that Germany was ahead with its own program, as warned by a group of leading scientists, with Albert Einstein as its spokesman.”

While Steve Reich’s musical score lay at the origin of Different Trains, it is the images and visual narrative that set the tone for the music of Out of Control, which Caravaggio herself commissioned from Danish musician Klaus Nielsen.

In Out of Control. Reports on the Atomic Bomb, the artist seeks to show the extreme precision, sophistication and control of science, as reflected in the numerous classified documents and films produced on the nuclear tests, set against the lack of control exemplified by the arms race, with the participation of countries of very different political and social regimes. A race that is out of control as the stock of arms only grows larger and larger. A product of scientific research that utterly escapes the control of the researchers themselves.

The start of the artistic and filmic project was preceded by a lengthy period of documentation and research into the materials available, as the artist immersed herself in the specialized literature on the development of the atomic bomb, its use on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the arms race that followed: “For me it has been an intense, revealing and, at the same time, moving process of study.”

“I was clear from the start which side of the story I wanted to tell. I didn’t want to tread the well-worn path, because the subject’s usual treatment in video and film is to focus on the research leading up to the bomb, the complex figure of Oppenheimer himself and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki detonations, and stop there. I was more interested in the position science adopts vis à vis other fields, because early on I came across Oppenheimer’s statement to the effect that being a scientist didn’t equip him to answer what should happen with the atomic bomb or how it should be used. He totally accepts that the “should” of values, ethics, means and ends be left entirely in other hands, those of the military and the politicians. I was struck by this refusal to engage in any real-time self-searching about the values and nature of the goals pursued, i.e., when engaged in a scientific project of potentially incalculable consequences, rather than with the knowledge of hindsight, and it’s one of the reasons I believe that certain major scientific projects should be framed by a dialogue with other cultural constructs, with the humanities and values, in which the scientific community participates alongside the public at large through a process of consultation with diverse social groups.”

Images of nuclear experiments

Nuclear tests are at the heart of the film: “They provide the connecting thread that runs through the various issues I want to touch on. I wanted to talk about the effects of nuclear weapons, firstly on people, but also on animals, ecosystems, nature and life,” its author remarks.

A section of the film deals with an accident in the Pacific during a U.S. test, whose casualties were a fishing boat crew. “This was an important incident, because it was again Japanese citizens who were exposed to radiation, but also because it brought proof that nuclear tests were going on, when they had so far been kept secret. The anger this caused was a factor in the birth of the anti-nuclear movement.”

Other images illustrate the widespread fear of nuclear deployment throughout the Cold War period, and the official rules and procedures designed in response, set out in what the Americans called “civil defense” campaigns telling the public how to “protect” themselves by building a shelter at home, or teaching schoolchildren and their teachers how to react in the event of a nuclear attack. “In Spain we are less familiar with these kinds of images or those of nuclear tests, because the nuclear threat and the Cold War have not been widely discussed or experienced directly, at least not to the same extent as in other countries. But now, with the war in Ukraine, it’s becoming a cause for concern. In other countries, certainly in the United States, these kinds of materials are better known, though perhaps a bit forgotten or unfamiliar to young people lucky enough to have grown up after the Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union.” In the wake of the Ukraine invasion, the media and some politicians are again talking about the tactical or even strategic nuclear threat.

From a formal standpoint, the artist has opted for a minimalist approach: “I think artworks should suggest rather than teach or directly issue calls for action, inviting the spectator in and allowing them to fit the pieces together in their own head and reach their own conclusion, without preaching. Another constant in my production is that I take care to avoid melodrama, especially with subjects as sensitive as this, because otherwise you can fall into the trap of sensationalism, which debases the work. It is more interesting for the spectator to see the images of utter devastation in Hiroshima on four screens, while listening to a Japanese voice reading out real witness accounts. When I let the protagonists speak, I prefer short phrases that are concise but say a lot. Maybe this traces back to Different Trains, which had a minimal script.”

“One of the key elements of the film is the contrast between scientific sophistication and the clinical detachment of the declassified papers – represented by a voice-over reading out extracts – and the human side of the survivors’ voices in Japanese.” This counterposition comes through strongly when, for instance, the voice-over concludes that the bombs performed as planned, with huge destructive efficiency, while the survivor recalls how “the outstretched hands of the bodies emerged from the rubble, as if begging to be saved.”

Creating a humanized work

“I knew along that I didn’t want to make a scientific or educational documentary. My goal was to create a humanized artwork where we can see that every one of us could be a victim, like the soldiers who were used as guinea pigs in some tests. Something that could, perhaps, elicit empathy with all those affected, potentially the whole world.”

The author was also concerned that the aesthetic impact of certain images should not blind the viewer to their meaning: “Some images are beautiful, but it’s a deceptive beauty; you can’t get carried away by them because it would be to trivialize the experience the film is depicting. The contrast with the test records helps in this respect, because it undercuts the impression of beauty. That’s why I use data like, for instance, the yield of an explosion, to place the image in context. Some of the most aesthetically striking images of a test are accompanied by the astounding fact that it was one of 35 atomic experiments conducted in the same spot in a period of just four months. That’s an outrage, a crime against the environment and animals; in fact, on on one of the screens we see an animal fleeing, which represents the danger to all life.”

A multi-channel format with four screens

The film is in a multi-channel format using four screens. This was a considered decision, driven by the desire to explore new creative paths: “In Out of Control, I wanted to investigate and test the limits, as all artists do. I wanted to see how far I could go with the use of archive material, but shown on four screens. The problem was how could the spectator take in that much visual information without tuning out. So I came up with a mathematical structure that made the material easier to assimilate: one of overlapping shots connected in pairs. What we have in fact are two nested diptychs in which screens 1 and 3 are related, on one hand, and screens 2 and 4, on the other. This creates the considerable difficulty of having to find images that work in pairs because, for instance, they are two takes of the same shot that last long enough to be superimposed.”

Asked what the language of video art can contribute to this narrative compared to mainstream cinematography, Caravaggio has this to say: “The lines separating audiovisual languages have grown increasingly blurred. Experimental filmmaking has always been with us, and for me, it’s what comes closest to what we now call video art, in that it is not a conventional way of telling the story, but one that allows you to experiment. Not to experiment for experiment’s sake, but to look for new ways to show what I want to say. The way I see and practise video art, it’s not a case of anything goes, where I pile on shots without rhyme or reason; it’s just that you have more room to experiment. The problem right now is that this kind of work does not make it onto the cinema circuits. A common argument is that the public won’t understand it, but I don’t agree. Films like Out of Control are for every kind of audience, and I use the word film advisedly, because it breaks down the barrier between video art and cinema.”

The film’s natural language is English. The declassified papers, the archive records used, i.e., the raw materials, are in English (except the Japanese of the survivors), with subtitles in Spanish. It will be on show in the BBVA Foundation’s Multiverso space, in Madrid, from June 2023 to June 2024 with free admission up to the room’s capacity.

It will then visit the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts in the frame of the joint program of support for video art creation of the museum and the BBVA Foundation.

Beatriz Caravaggio

Born in Oviedo, she graduated in English Studies from her hometown university. She then moved to Madrid, where she studied music and cinematography. The focus of her artistic and professional activity is primarily video art and non-fiction film. Her work includes video installations, creative documentaries, photography and net art. Among the venues where her works have been shown are: the Museum of Fine Arts in Bilbao, Fundació Joan Miró and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània in Barcelona; Museo Reina Sofía, La Casa Encendida, Círculo de Bellas Artes and MediaLab Prado in Madrid; the Patio Herreriano Museum in Valladolid; the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, United States; the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity and Soundstreams (Toronto) in Canada; the Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth in Australia; and Rockport Chamber Music in Massachusetts, United States. She has received a number of awards and grants, including a film production grant from the Spanish Film and Audiovisual Arts Institute (ICAA); a creative grant from the Centro de Creación Contemporánea Matadero Madrid; the Oscil.lant Award from Festival Mínima for ¿Por qué mutan las moscas mecánicas? and the Net.Art Visual Prize for her work Cartografía de la sospecha.